Beyond ensuring that the name for each image is unique, a filename

may help you retrieve an image from its location, and let you know where the

physical "original" is to be refiled. In some filing systems it

may include additional information about the image that you can tell at a

glance. In terms of an image database it has another function, to act as a

"hook" to hang additional information, such as meta-data (literally,

"data about data") regarding an image. In addition to a description

of the image, this might include items such as keywords to find the image,

where the image was taken, when it was taken, model or property releases and

more.

If you are working with a digital camera, you may wish to sort

your images into folders and then automatically rename as a batch function.

If you are using Photoshop 7, there's a fairly simple way to "batch-auto-rename"

using the file browser. This works similarly with the filebrowser that comes

with CS, or Bridge wiht CS2/CS3.

Think Virtual Storage First

What I tried to do was create a system that will allow me to give

each slide, negative, or digital image a unique name, and keep it within

7 characters. Why not eight? Well, in order to allow more than one version

of a file to exist in the same hard drive folder the name must be different

by at least one character or number. By using 7 characters to refer to the

physical film, the last digit can be reserved to distinguish between variations

of a single image.

Create a Subject List For Your

Slides

Since slides come in separate cardboard mounts most photographers

tend to sort and edit out the bad exposures. Afterwards it's easy to put

like subjects together. You probably have some scheme already in place that

you may use for your slides. Use that system and build on upon it to cover

all the possibilities you can think of. I came up with a list of about twenty

primary subject areas, and wrote them out in order. In order to save space

in the filename, I broke each down to a two letter code--Agriculture became

ag, Animals turned into an,

People was shortened to pe. Use your imagination;

you probably don't shoot the same subjects I do so my codes may not be of

benefit to you. I do write these all as "lower-case" letters to

avoid confusing zeros "0" with the letter "O" and though

you have to be careful with your lower case letter "l" and the

number "1" as they can look very familar.

This same system of subjects will be used to store your digital

files. You will have to make judgement calls on some images. An image of

a cow in a field could go in either Animal or Agriculture. If the image

is primarily of the cow, I'd go with AN, if it's an establishing shot that

shows the field, a stream, and the sky as well as a cow, I might decide

to put it under AG. Once the image is placed into the image database the

meta-data can be used to "cross-reference" the image by describing

all the other possible uses for the image, so don't get too hung up on which

physical location, or folder on the hard drive that you choose.

Physical Storage Segues to Virtual

After 35mm slides from each subject area mentioned above are assigne

a category, they are placed into 20 slide-per-page hanging files. Each page

is given the 2 letter code and a 3 digit sequential page number (001, 002,

etc). Each position on the page (1 to 20 for 35mm) can be given a number

as well. Thus each slide has a unique name/number and each name/number tells

me where it is located. The first slide in the AG page would be AG00101.

PE10020, would be the slide on page 100 of people section in the 20th position.

Everybody has their own way for storing negatives. For about

the last ten years I've been storing each sheet of sleeved negatives, sequentially.

I had started out with 4 digits, but expanded that to five by adding a 0

(zero) in front of all the old numbers. That means when I get to 99999 I'm

either going to have my own personal Y2K crisis, or I'll have to retire!

Other photographers have used the year, month, day (YYMMDD), combination

of year and sequential number (YY001 or YYYY001), or other

name and number combinations.

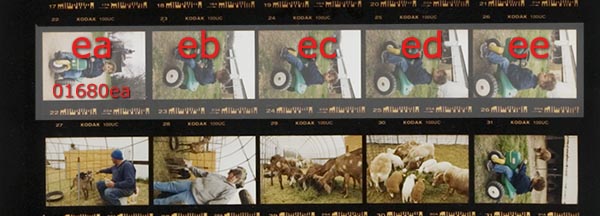

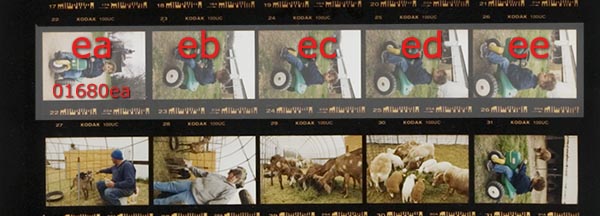

Usually when photographers refer to contact sheets we will

use frame numbers, but in order to avoid "a" frames (where the image falls

halfway between two numbers), I opted, instead, to use letters. The first

letter represents the row, and the second the position within that row.

So the first frame of the first row could be written as "aa" and the fifth

frame of the 4th row would be "de." The added advantage is that

mixing the letters and numbers makes the filename a little easier to remember

than a string of seven numbers.

This is also a benefit if you are working with older medium

format or large format film, as some don't contain any frame numbers. I

shoot a lot of bulk rolled B&W infra-red film and it doesn't have any

edge numbering at all. With this system it doesn't matter, as I'm going

by the image position on the contact sheet to ensure that each image has

a unique name. If you shoot medium or large format transparencies and store

them in plastic sleeves this may be a better option for storing and numbering.

If you have historical prints with no original negative you may wish to

use something similar to the method described above for 35mm slides.

The "Mystery" character

If you've been following so far you'll see that I've only used

seven characters or numbers to describe each image. However, in the beginning

I mentioned that the system was set up to subscribe to the legacy 8.3 DOS

filenaming convention. This is for two reasons. The first is that most

people

have trouble remembering more than 7 numbers or characters. You've probably

heard of the "seven

plus or minus two" rule. It dictates the amount of information

that the average person can store in their short term memory according

to

a 1956

study (alternate

source for 1956 study which includes German and Russian translations)

by

psychologist, George

Miller.(note that there are number of articles which refute

Miller's study as well, but in practical use I think it's important

to note that most people will have trouble remembering

filenames as they are made longer). The second reason is because

that last "mystery" character

is used to distinguish each version of the digital scans. I refer to

this as

the image "suffix" and the code for each of those I use is below..

My "suffix" code:

a= Access (low res file for FPO use)

If from photo cd then it's the same as Photo-cd Base resolution- 512 x 768

pixels, if from sprintscan or other scanner usually saved as a 6 x 9 to

8 x 12 inch image at 72ppi. (since it's the first letter of the alphabet

it will show up first when you do a search in an image database or with

filefind or sherlock).

b = Black & white (any file in grayscale color

space)

c = CMYK (any file in this color space)

d = Digital

f = Photo-cd scan (Full resolution, Base*16 resolution,

2048 x 3072 pixels)

h = Photo-cd scan (High resolution, Base*4 resolution,

1024 x 1536 pixels)

l = Lab or CIElab color (an archive file in the

widest possible color space)

p = Photo-cd scan (Pro resolution, Base*64 resolution,

4096 x 6144 pixels)

r = RGB (generally an archive image or largest possible

file size for that format)

s = sRGB (often an access file converted to sRGB

for use in PowerPoint, or other applications that are not color management

savvy)

w= World wide web usage (images that are web ready,

stored as Grayscale or RGB.JPG)

Feel free to create your own system for the types of files

you use if these don't work for you.

I use standard file extensions on all image files as if they

get e-mailed, uploaded to a web page or burned to cd-rom they will already

be cross-platform compatible..PSD for photoshop layered files, .TIF

for TIFF files, .EPS for Encapsulated PostScript, .JPG for

JPEG images, and .GIF for 256 color, Graphic Interchange Format.

The Form has a Function

So each scanned image follows the form [UID] [suffix].[extension]

and thus, all subscribe to the older windows 8.3 file format standard. You

can burn all your images to a CD ROM using the ISO-9660 level 1 standard

and it will be readable on Macs, PCs, Unix, and even amiga machines.

Slides

Example: an02002[suffix].[ext]

an = Animal section, 020 = page #, 02

= position #

click

to enlarge

Negatives

Example: 12035gd[suffix].[ext]

Negative filing number(five digits), followed by two letters representing

row and frame. In a roll of film cut to seven strips of five frames, there

would be 7 rows (A to G) and five frames (A to E) so first frame would be

aa and last would be gd. Six rows of six, would be aa

to ff. Using letters avoids confusion in determining the file number

from page position, and only requires two spaces (often the center of the

frame ends up as 1a, rather than 1).

click

to enlarge

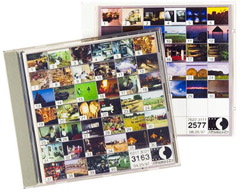

Photo-cd files

Example: 0340-01[suffix].[ext]

As I also have a sizeable number of images already scanned

in the Kodak Master and Pro Photo-cd format, I've added another type of

filename. For this I use a modified version of the disc number and frame

number to identify the source of the file.

The first 4 numbers are the last four digits from the Photo-cd

jewel case (in large bold type, here it's disc #0340) the second two represent

the image or frame number as printed on the index print.

As these are from negs or slides, the actual location of the

original can be noted in the "Title" field of the IPTC/File

Info section of the image. Which, did I mention before, most

image databases will gather this IPTC metadata automatically?

click

to enlarge

Digital Camera files

Example: pe10500[suffix].[ext]

pe = People section, 10500 = the 10,500th

image in the People folder on your hard drive.

Keeping the letters all "lower case" makes it harder

to confuse an "o" with a "0" (zero).

If you need to apply your filenaming scheme to a number of

existing images, you can do so using the "batch-auto-rename"

feature of the file browser in Photoshop 7.

Once you come up with a system that works for you then you

are ready to prepare your images for meta-data encoding. This might include

putting appropriate keywords and descriptions into your TIF or Jpeg files

using the File Info feature within Photoshop, or an external program such

as the Image Info Toolkit,

or Photo

Mechanic. In addition you may want to read how you can automatically

have your filename written into the Title field of your IPTC metadata,

as a way of identifying images in case someone changes the filename.

For another perspective, read Ernest H. Robl's article, Image

Numbering, Filing, and Retrieval that was originally prepared for

the American Society of Picture Professionals (ASPP) site.